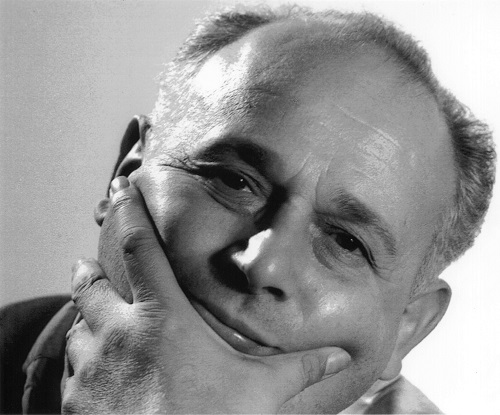

Moshe Feldenkrais – the Man and his Method

Moshe Feldenkrais was a remarkable man. Born at the beginning of the 20th Century, his long and fascinating life is instructive on what his method aims to achieve. He travelled extensively from an early age. He carried out a wide variety of different work from teacher to labourer to scientist to writer (acting was next on the list.) And he integrated this enormous variety of experience and knowledge to develop his life’s work.

He grew up in what is now the Ukraine, part of the extensive Jewish community which then existed, in the time leading up to the First World War. Feldenkrais was not a religious man, but his upbringing in a culture steeped in Hasidic Judaism had a profound influence on his life. As Mark Reese says in his biography of Feldenkrais (2015: p2): ‘Untrammeled expectations can be the healer’s or the teacher’s greatest gift’. This is reflected in the optimism he brought to the practice of his method – an unerring positivity in situations which others might regard as hopeless. One of the ways he defined the concept of ‘health’ was the pursuit of one’s ‘unavowed’ dreams (‘unavowed’ in the sense of the dreams we haven’t yet promised or admitted to ourselves.)

As Reese goes onto explain Feldenkrais also inherited from his ancestor – the eminent scholar Rabbi Pinhas of Korets (p6): ‘the conviction that students must learn from their experiences because we learn the most significant lessons from attention to our own lives.’ As Reese explains they both eschewed traditional teacher / student relationships: prompting questions was more important than providing answers directly. These elements are at the core of Feldenkrais, the method, today.

Perhaps belying initial appearances as ‘alternative’, Moshe devised his practice as an eminent scientist. Building on his scholarly inheritance, he excelled at his studies as young man in Palestine, winning a scholarship to study physics at the Sorbonne, in Paris. He soon showed himself to be a precocious student, working in the nuclear laboratories of Frederic Joliot-Curie at the College de France.

After fleeing the Nazi’s in France, he worked for the British Admiralty on sonar systems. And the publication of his book Body and Mature Behaviour in 1949 received significant acclaim from the medical and scientific communities. Feldenkrais’s insights into the nervous system – suggesting that it is much more amenable to change, including later on life – predated current science on neuroplasticity by several decades.

Indeed, a scientific framework underpins Feldenkrais lessons today – each could be characterised as a series of ‘experiments’ with the student, initiated by the teacher. The teacher brings to the student’s attention an area of enquiry, a baseline. One by one the teacher and/or student make discrete movements – changes are made – the interest or validity of which can then be compared to the baseline. Areas of pain, for example, can be explored in this way and the student can become more aware and able to identify how to make their movements and everyday activities easier.

Finally, in addition to his Jewish background and scientific prowess, Moshe drew heavily on his athletic endeavours. Shortly after moving to Palestine, he became interested in self-defence and soon began to teach members of the Jewish community how to defend themselves in hand-to-hand combat. In Paris, Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, recognised Feldenkrais’s potential and enlisted him to introduce Judo to France. He became a leading practitioner and writer in the field.

In the practice of Feldenkrais today, there is an emphasis on what Feldenkrais termed ‘reversible’ movement. The idea is that students should aim to move in such a way that at any given time they can reverse the movement, and move in a different direction; that one should not be so committed to a movement that it can’t be changed at any time. A useful attribute, no doubt, in a martial arts context, where swift changes in direction may be key in defence or attach.

A central element of the method is to enable people to eliminate compulsive movements, and actions. The objective is to have the self-awareness to thereby be able to control oneself and not be motivated by force of habit; to know how to move (and be) in an optimal way, and to be able to put this knowledge into practice.

References:

Feldenkrais, M (1949) Body and Mature Behaviour: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation and Learning. New York: International Universities Press.

Reese, M (2015) Moshe Feldenkrais: A Life in Movement, Volume 1. San Rafael: ReeseKress Somatics Press

Ed Bartram, March 2022